Let’s talk about Upper and Lower Crossed Syndrome…

I won’t go too far down the rabbit hole with this introduction, but one thing the biomedical model and insurance companies have pushed in healthcare, is putting a label on everyone who comes through the clinic door with pain. Whether you’re a chiropractor, physical therapist, athletic trainer, or any other healthcare professional, most of us are taught early on to diagnose every painful pathology.

From the point of view of a healthcare professional, I get it. In theory, a diagnosis usually comes with a set of exercises, ready-made for that particular diagnosis (sounds simple enough).

From a patient’s point of view, I get it. If you’re having pain, you probably want a diagnosis, or label that will help explain your pain. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll stick with common overuse issues w/ household nicknames, SOME of these being helpful in identifying the issue to be able to best attack a rehab plan.

A few of these that some of us may have heard before include:

• Tennis Elbow

• Golfer’s Elbow

• Jumper’s Knee

• Runner’s Knee

• Piriformis Syndrome

• Shin Splints

• Text Neck (just kidding, I hope this never becomes a label…maybe another blog in the future)

Alright, where am I going with this…I thought we were talking about something called Upper and Lower Crossed Syndrome! Well, let’s get into it. Where did this other syndrome come from and is it contagious? (kidding)

What ARE Upper and Lower Crossed Syndromes?

These terms were coined in 1987 by Dr. Vladimir Janda, a Czech doctor and researcher. It’s basically a theory on how “poor” or slouched posture will lead to pain.

There are lots of theories out there like this one, but Janda takes this one a bit further. Janda and researchers attempt to combine muscle imbalances, posture, and a clinical story on how to predict future pain, compensation, and injury.

I’ll let Janda explain his theory…

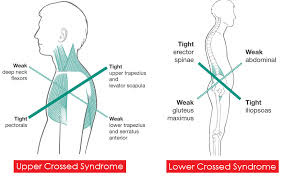

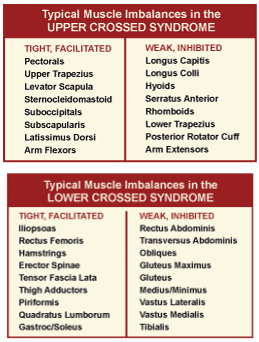

“ Over time, these imbalances will spread throughout the muscular system in a predictable manner. Janda has classified these patterns as “Upper Crossed Syndrome” (UCS), “Lower Crossed Syndrome” (LCS), and “Layer Syndrome” (LS) (Janda, 1987, 1988). [UCS is also known as “cervical crossed syndrome”; LCS is also known as “pelvic crossed syndrome; and LS is also known as “stratification syndrome.”] Crossed syndromes are characterized by alternating sides of inhibition and facilitation in the upper quarter and lower quarter. Upper crossed syndrome is characterized by facilitation of the upper trapezius, levator, sternocleidomastoid, and pectoralis muscles, as well as inhibition of the deep cervical flexors, lower trapezius, and serratus anterior. Lower crossed syndrome is characterized by facilitation of the thoraco-lumbar extensors, rectus femoris, and iliopsoas, as well as inhibition of the abdominals (particularly transversus abdominus) and the gluteal muscles. (Jandaapproach.com)

The idea here is that our body will follow the path of least resistance, and if we sit too much, over time there will be very specific consequences.

These below pictures may help:

Image from foundationpilates.com

Image from SgPhysio

One issue with this theory is that it sort of makes sense, so I get why people cling to it. The problem with this theory is that it doesn’t take into account normal human variability (everyone has different spinal curvatures genetically and overtime), and it has never been validated.

Words like, “facilitation”, and “inhibition” sound technical and specific, but the problem here is that they aren’t. If we’re talking about inhibition after surgery, that’s different.

Otherwise, these are terms that aren’t well understood in the medical community, and never defined the same.

The “tightness” of muscles doesn’t seem to have much to do with their strength, or with pain, or really anything that anyone can actually work with. If certain muscles were actually weak in everyone with Janda’s head forward/slouching posture model, and those people tended to have certain problems, then it would make sense to try to strengthen those muscles specifically. But it doesn’t seem to work that way.

Treating people as if they have Upper Crossed Syndrome — with targeted stretching, strengthening, and massage, doesn’t work any better than generally getting more exercise and moving into different postures or positions throughout the day.

Don’t just take my word for it, below are some examples from the literature. I’ll highlight 3 studies to help get the point across, although there are a few hundred more we could point to.

Richards et al, 2021, showed a group (over 100) of young adults with different neck/mid-back postures, and low and behold, the group with the forward head posture had less incidence of reported neck pain, and the group with a more erect/straight posture was linked to a higher incidence of reported pain. This isn’t to argue that you SHOULD sit like this, just that pain and “dysfunction” are highly variable.

Referring mostly to “Lower Crossed Syndrome”, Heino et al 1990 (an oldie but a goodie) attempts to show the relationship between hip extension (“tight” hip flexors), postural alignment, and “weak” abdominals. We’ll fast forward through this one, there IS NO relationship.

This is just one study, but this has been replicated a few times across different studies with the same conclusion. This means, the idea that the symptoms of “Lower Crossed Syndrome”, which include certain standing postures being linked to weak abs and tight hip flexors, just don’t exist.

Again, referring to “Lower Crossed Syndrome”, Mills et al, 2015, attempted to show a relationship between hip flexor “tightness” and glute strength, and in doing so still came to the same conclusion as above.

There was no relationship. The study was performed on female collegiate soccer players, and grouped between those exhibiting less hip flexor range of motion and those with more, but glute strength numbers were all over the board.

In conclusion

In conclusion, I think Janda probably did the best he could with the data he had at hand. When theories like this continue to come out, I think it’s a slap in the face to us as resilient people and to our nervous system.

We will always find ways to adapt, everyone is different, and it is impossible to put large groups of people into their own box in hopes that it will simplify healthcare. There are lots of reasons why exercise and “strengthening” exercises may help with pain, some are physical, some chemical, some psychological.

Either way, you can’t go wrong being strong, and the best posture is being able to get into and out of lots of different positions.

If you or someone you know is struggling to identify the source of their pain, and they’re frustrated with any one-size-fits-all approach they may have encountered in the past, we at Tangelo Health would be honored to help in any way we can.